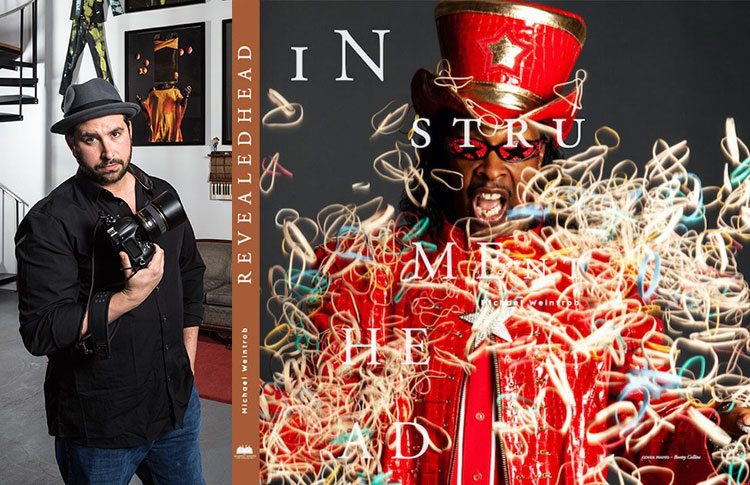

Photos Courtesy of Michael Weintrob

The Nashville photographer & author is crowdfunding Instrumenthead’s companion book, with donors receiving special incentives. Once published, $3 of every book sale will be donated to the New Orleans Music Clinic.

“Do something crazy — put your bass down your shirt!” Michael Weintrob shouted to Todd Smallie, bassist in the Derek Trucks Band, as he came down the stairs. Trying to loosen up the band before their photoshoot, Michael never could have imagined how much that spontaneous moment would shape his future career.

Over the following two decades, Michael photographed hundreds of musicians and developed his own unique style. Formerly an exclusively live music photographer, he sought to find his personal voice in portrait studio photography.

Inspired by his shoot with the Derek Trucks Band, he did it with Instrumenthead. Since that first shot of bass-headed Todd Smallie in 2000, he has taken iconic photographs of musicians, where their faces are covered with their instruments — “To show where their heads are really at,” in Michael’s own words.

With a touring gallery since 2013 and the Instrumenthead collection published as a book in 2018, the world has fallen in love with Michael’s work. One comment he has received repeatedly after Instrumenthead, though, was “I wish I could see their faces.” It’s easy to see why, as the portraits are such an intimate expression of the musicians’ personalities.

Enter Instrumenthead Revealed, Michael’s follow-up book. The new collection features photos from the same shoots, without obscuring the musicians’ faces. The artists are shown in the same order as in Instrumenthead, making it the perfect companion book to get to know these intriguing characters more personally.

Besides being one of today’s most sought-after music photographers with over 20 years of high-profile experience, Michael is one of the kindest people you will ever meet. He always seeks to pay it forward, and he is immensely grateful for all the support he has gotten over the years to make it all possible.

After turning away from major publishers, Instrumenthead was crowd-funded so that it could be independently published, and Instrumenthead Revealed is similarly crowd-funded. It’s nearing the end of its campaign, and it’s already reached its $65,000 goal.

You can contribute to the Instrumenthead Revealed publishing campaign and preorder a book here. Always seeking to support others, $3 of every book purchase will be donated to the New Orleans Musicians’ Clinic.

Binaural Records contributor Andrew Fletcher had the opportunity to sit down with Michael and gather his thoughts on his work and most recent book, Instrumenthead Revealed. Read on to hear Michael’s inspiring story.

Interview with Instrumenthead’s Michael Weintrob

Andrew Fletcher: Michael, thanks for taking the time out to talk to us today.

Michael Weintrob: Yeah man, you bet. Glad to be here.

Tell us more about your backstory — what got you into photography, and how’d you get your start?

I’ve been a rock ‘n’ roll photographer since I was 19. I came up in Fort Collins, Colorado, where I was the house photographer at the Aggie Theater, shooting live shows. Eventually I became a house photographer at Red Rocks in the late 90s, and then I moved to New York City and lived there for 13 years, starting a studio. I’ve lived in Nashville for the past seven years.

And you’re still doing the same stuff there, shooting local shows and bands?

Yeah, but it’s more national now though. I still go on the road a lot, and I shoot bands everywhere. Just yesterday I had a shoot with Dumpstaphunk.

Oh nice, I just saw them in Denver a little over a week ago.

It was epic, man. Marcus King sat in, and it was such a great show. I do a lot of that kind of stuff. I shoot concerts, and I’ve been traveling around.

I was always a live music guy, and I got to do some cool stuff. I was in Denver and I shot Pearl Jam in 2003 when George Bush was running for office, and Eddie came out and did the “Bu$hleaguer” thing with the head; he put the Bush mask on the mic stand and put it up on the thing and slammed it on the ground, stepped on it. I got photos of all that, and I think that ran in Rolling Stone, actually. And so I was always a live music photographer.

When I moved to New York, I met with editors at Vibe and Spin and Rolling Stone and they all said, nice, your live music stuff is as good as it gets. But if you want to be a portrait photographer, you need to find your voice. And I had taken a few Instrumenthead photos before and this is where I’ve found my voice, through this project.

I wanted to travel around creating these immersive music and art experiences where I got to show my work. I was calling all these festival promoters to exhibit my stuff, but eventually I just said, “Screw it, I’m just going to create my own thing. I’ll go to Jazz Fest in New Orleans and create these big art exhibits and have the bands and the photos perform.” Bring the photos to life, you know? That’s how it all started.

I made this book, and it went to print twice. I printed around 4,000 copies of Instrumenthead, and I still have about eight or nine hundred of them in my basement. And with COVID, I haven’t been on the road doing stuff, so I had time to put together something new.

So hence, Instrumenthead Revealed.

Yeah. Everyone always told me they wanted to see the musicians’ faces. What people didn’t realize is that I would do these massive, huge photoshoots for an hour, two hours in the studio. Instrumenthead only took like, three minutes, because it’s torture for them, you know? But that was a vessel to create all this other stuff.

So COVID was a good excuse to put together the next collection. I went through all the stuff and made my new book, and now it’s coming together! Three weeks ago, I launched a crowdfunding campaign for the new book, which is called Instrumenthead Revealed. And I’m really optimistic that I’m going to reach my goal, which is awesome. I’m supporting the New Orleans Musicians’ Clinic who give health care to musicians down there.

Tell me more about that — what is the New Orleans Musicians’ Clinic and what do they do?

So they’ve got an actual clinic, a walk-in clinic doctor’s office where people can go. But they also do stuff with mental illness and therapy and that sort of thing. During COVID they also created a meal train. They’re just really supportive to the community down there.

Specifically for the musicians?

For the musicians, yeah. I mean, I think other people can go to the clinic as well, maybe. But they’ve got money to be able to help some of these guys and keep them alive. Because they’re not always the healthiest down there.

Yeah, it’s a huge scene, with so many people trying to make it. Nashville too, I bet.

Totally, yeah. It’s just nice to meet a charity that actually does what they say they’re gonna do with the money, you know?

Absolutely. How long have you been working with them?

I’ve been working with them for around 15 years, and I’ve probably raised almost $20,000 for them personally over that time. I go and do these exhibits, and I give a piece. Sometimes I’ll do art sales, where I’ll split the money with the musician in the photo and the charity. We split the money three ways. I’m always just trying to figure out a way for us to empower one another.

Basically it’s just, I sell artwork, and I sell things. It’s good to have a charity tied to it. I feel really good about giving back to the community in some way.

Yeah, like a “pay it forward” sort of mentality.

For sure. I’m a big believer in karma. Give to give, not give to get. So I started a relationship with the clinic in 2005, and in 2013, we did this really big, huge show in New Orleans where over 7,000 people came, and they were one of the beneficiaries of that.

Wow, how did you pull that off?

It’s a long story, actually. I remember I was in Seattle, and I walked into a record store and I saw a life size cut out of Q-Tip with his MPC instrument over his head. Before that I had approached Q-Tip and said, want to do this photoshoot? He kind of blew me off, and Danny Clinch ended up shooting it. And then Danny also did a portrait of Eddie [Vedder], with his ukulele over his head that was on the cover of his solo record.

I met Danny and I showed him what I was doing with my Instrumenthead photos. And he’s like, oh, that’s cool. Then another time, someone contacted me and they said, “Hey, nice photo in Mojo magazine.” It was a full-page shot of Dan Deacon and he had his instrument and he was shot in gray. It was the same way that I did it, but I didn’t shoot it. I freaked out and called my lawyer, and all of a sudden, I’m sending all these cease-and-desist letters, because these people had taken my idea!

Then I realized, these letters aren’t going to fix anything — I just need to have an exhibit. And I need to do it in New Orleans because I’ve been going there for 20 years to Jazz Fest, and I love it there.

A friend of mine gave me a 50,000 square foot warehouse to use — we transformed a giant warehouse where they kept trash into a legit art gallery! It was the first show that we ever did, back in 2013.

And, you know, we were really down to the wire. I remember we were putting hardware in the back, and I went to Birmingham, Alabama, wrapped up 75 four foot tall photographs with bubble wrap, put them in a U-Haul truck, drove it to New Orleans, and went to this warehouse where my friend had built these drywall cubes and walls that were waiting for us. It was supposed to open on Wednesday, and this is Monday night at four in the morning. We’re putting hardware in the back of frames. We got to the last one, and then it was leaned up against the wall. The wall starts to fall. Now I’m holding up the wall. We start to move all the prints up against the brick wall. We finally got home to sleep at eight in the morning, and then our phones started blowing up saying there was a tropical storm coming through New Orleans and the warehouse was flooding. So then we had to run back and put up all the stuff. We had to put everything on tables, and it was a complete shit show. It was nuts!

Holy cow, anything that could go wrong did, it sounds like.

But it all worked. We didn’t lose anything through all this, all of the photos were still good to go, and we managed to make it work. And then we had over 7,000 people come and see it, and they loved it. It was in this location where people were there, but they didn’t even know how they got there, haha! It was at the end of a 100-vendor art market where all these people were selling their stuff. And then we were in the warehouse in the back. People were strolling, and they just ended up there.

It was the start of my new life of being able to sell my art, because as an artist, if you can figure out a way to sell your art, you can create freedom, right? Because what happens is your fingers break, and you can’t play the guitar anymore, or I can’t take a photo anymore. So you have to figure out ways to create freedom to be able to continue doing art. And that’s what this allowed me to do, which is pretty amazing. Eventually we plan to help other artists who have big bodies of work put their books out, and empower them to be able to have real freedom too.

InstrumentHead – New Orleans 2013 from Jakprints, Inc on Vimeo.

And this was in 2013? What changed?

Yeah. Up until that point, I hadn’t been showing anyone the work. I was too paranoid of people stealing my ideas… but then they did anyway. So I figured, what the hell, it’s time to take this on the road. I started doing shows like that around the country after that.

So was Instrumenthead kind of like a side project before that, while you were still mostly doing concert photography?

Yeah. When I moved to New York in the 2000s, I moved into this building filled with artists and photographers and filmmakers. A lot of them were assistants to assistants of Mark Seliger, Steven Klein, and Ann Liebowitz and all these famous photographers. These guys were my bros and my neighbors, and they taught me how to be a portrait photographer and find my voice. So I would hire them to help out when I would do shoots.

I started getting pretty successful, and I would get offered jobs. And I became the king of losing jobs. I thought that I had to get paid $5,000 to click a button. There was a woman named Connie Crothers who lived below me who was one of those jazz prodigies. She was playing swing all day, and it was like the soundtrack to my New York life. And she said she wanted to do a photoshoot. I gave her a price, like 750 bucks. I thought that was the bro deal of all time, since I had been charging so much more. And she said, well, I can’t afford that.

I had a realization: do I have a photo studio, or do I have a really expensive storage closet? I realized the photos were more important than the money. So I called all my friends who were musicians and said come on over, let’s do this. I’ll give you free promo shots and trade. It’ll be about art. And so Instrumenthead became a vessel to create my voice as a portrait photographer, because photography is about telling stories, right? I shot them with all their stuff for free, for them to use and be proud of, just to get some more experience. I didn’t even know I was working, but after a while, I had hundreds of these Instrumenthead photos.

What inspired you to keep doing the Instrumenthead photos, in particular?

I distinctly remember walking into this bookstore in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in 2008, and I found this book called The Disciples. Want to see it?

Sure! That’s cool that you still have it.

[Michael runs and grabs his 13-year old copy of The Disciples]

See, it’s got all these logos of these bands on the cover. It’s pretty intriguing. When you open the book, it’s all photographs — fans of bands. Disciples, if you will. The whole idea is when you look at the photos… See, here’s a Missy Elliott fan. Can you guess who these guys are fans of?

[Zoom was not meant for this]

Uh, I can’t really see too clearly… not sure.

Snoop Dogg!

Oh, I see it now.

And then Morrissey. They all look like the people in the band, right? ZZ Top fans have beards. Wailers fans have dreadlocks, Jimmy Buffett fans wear grass skirts.

You attract what you are, as they say.

Totally. And I was thinking, how can I create a guessing game with the musicians? I have all these photos of them with their instruments over their heads, and even though you can’t see who they are, you can feel their personality. So I started focusing on that a lot more. Then the next question became, okay, how am I going to get more of these photos? That was where giving them free promo shots started coming in. Just call them up and see how we can help each other. So that’s kind of how it all started.

I started traveling around the country, using music venues as my studio, because they had big open rooms that were empty during the day. And I would call my friends and say, “Hey, who do you know that’s known for their style or their instrument? Tell them to come down. Let’s do a shoot.” So I just really put in the time around then. Then I started doing these exhibits and it was like I was a touring musician. I’m like a musician, but I have a camera instead. And I run my business the same way a musician would, I just have more shit to load in and less people to do it!

Hahah, yeah. It’s inspiring to hear that this work that you’ve become so well-known for actually just started as a project to help others and do something cool.

That’s what I’m all about, man. I just want to make cool stuff. The money doesn’t matter. If you do a good job, it’ll come eventually anyway. But for now, just do what you love.

Yeah. And it sounds like you’ve really built a big network along the way. Is that why you chose to crowdfund the publishing for Instrumenthead and Instrumenthead Revealed?

Kind of. I was living in New York and I met with editors at HarperCollins and Glitterati, and all these big art book publishers. And they were all wondering, how are we going to sell it? Who are the most famous people in this book? But that was never the point for me. The photos are about so many of the sidemen, to highlight the ones who do a ton of work but who don’t always get much credit. And we had been doing all of these art shows and galleries, and they were pretty successful, so I took my chances and crowdfunded to self-publish Instrumenthead. It was a huge success, and it connected me with the right people to publish Instrumenthead Revealed. I have a better idea of the process this time around.

That’s awesome. How have you promoted the new book with COVID going on? I can’t imagine there are many art shows these days.

Right. I have some plans for later this year — I’ll be at Jazz Fest in October, doing another pop-up, for instance. But I’m only just starting the in-person stuff again.

I remember reading about Instrumenthead Live — tell us more about that.

Sure! So a buddy of mine was the front-of-house engineer for Greensky Bluegrass for around a decade, and he has all this gear. When COVID started he came and installed like their whole tour rig, and even a lighting truss in my studio. The only thing that was missing was the cameraman and cameras, because we’re photographers, not video people. So we got a couple directors and people who own gear to come in. Eventually, we met this guy who’s a TV director for Good Morning America and The Today Show — he’s a huge Deadhead and just did the inauguration for Joe Biden. And he loves live music, so he agreed to come down and direct all the shows, and he put a ton of money into it. He bought all the cameras.

All of a sudden, we’ve got great audio, we’ve got great video. And then in March, Paste magazine came in. They do these on-the-road shows. So we started doing these shows and doing things like a Molly Tuttle CD release party, that sort of thing. Basically, we made ourselves a venue. There were 28 concerts in seven days here, and the musicians streamed it live to their people — tons of famous musicians. And I thought, well, why don’t we do something like that for my crowdfunding campaign?

Ah. And thus, Instrumenthead Live was born.

Yeah. So in March for five days and for two days in April, we had 20 bands coming here to record shows. I was going to release the Instrumenthead Revealed campaign on April 28, but it took me till June 22, because we had to edit all the videos, and I had a graphic artist help create illustrations of all the musicians. And so we’ve basically just been putting it out there for the past month to promote the campaign. And the musicians did it for me, and we used the shows as a vehicle for crowdfunding. To be honest, I have no idea how much it’s helped. But I’m just stoked to create cool stuff with people and let people use my space as a place to create. And that’s what we did in COVID.

It’s like my studio became like the shrimp boat in Forrest Gump. You know what I’m talking about? All the shrimp boats got destroyed, and then they started catching all the shrimp. I had an agent from William Morris call me to try to book a band for my photo studio. There were no places for anyone to play. So we did it. It was awesome. I saw 70 concerts in the last year and a half.

Wow, that’s amazing!

Yeah, and it was really special, because it was just us and the band, recording it. Are you an Allman Brothers fan?

Love ‘em.

Okay, so we have our last show getting released on July 21st and it’s with Peter Levin, he’s the organ player that played with Greg Allman, and Marcus King. And Jimbo Hart from Jason Isbell’s band and Lamar Williams Jr. singing — his dad was in the Allmans. So first they did their set for 30 minutes, “Born Under A Bad Sign” and stuff like that. And then I said, well, why don’t you do an Allmans tribute? And he calls Audley Freed. Audley used to be in The Black Crowes. And anyway, he came over and they did “Ain’t Wastin’ No More Time,” “Statesboro Blues,” “Whipping Post,” “Dreams,” and “In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed.” It was 11 o’clock on a Tuesday morning and there were three of us in the room. It was the most epic show ever. We have the video but we haven’t released it yet, because he called the managers to tell them and they’re like, did you get the publishing so now we’re trying to figure out all that. Yeah, it’s fun to say, just come on down — we have all this stuff.

Did Instrumenthead Live help fund Instrumenthead Revealed?

At first our business model was to get the bands who had big followings to sell tickets, like we had Robin Ford and Jeff Coffin. But we got locked on the paywall. Nobody bought tickets, because they couldn’t figure out how to get through the paywall. So then we realized, we’re gonna give it away for free. We’ll just do tips, because if you tell someone to spend $10, they don’t want to do it, but if you give it away for free, they’ll give you $20. So we just started doing that. And we kind of broke even, but it was really just a fun project to do during COVID. And so this whole Instrumenthead Live thing is now a living vehicle. You know, it’s much greater than me.

And that’s all at your studio in Nashville, but you take it on the road with the gallery too, right?

Yeah, whenever we would do the gallery, we would have live music too. But it wasn’t called Instrumenthead Live — those are all from the studio here in Nashville. You can watch those on YouTube, actually.

That’s super cool. I like how you’ve managed to blend the photography with the music, especially live at the exhibits. Your work stands out to me because it’s such a personal, visual capturing of the music, instead of just being auditory. I think it’s really groundbreaking.

Thanks, man. Yeah, I mean, when you’ve worked for a million hours on something like that and don’t stop, eventually you become pretty good at it. Do you see this mural of Ray Charles behind me?

Yeah.

I shot that photo in 2001 at the Paramount Theatre in Denver and people started coming up to me and saying “That’s the best photo I’ve ever seen!” So I thought to myself, “Okay. I’m gonna be a music photographer.” I just never quit. Even in college, I was doing it.

Nice. Well, it shows!

I love what I do, and I’m grateful for all the support I’ve gotten that’s allowed me to keep doing what I’m doing and keep getting better at it throughout my life.

That’s a great perspective. How do you capture a great photo? Do you take hundreds, or thousands, of photos in a shoot?

Yeah, maybe in the beginning I did that. I would take so many photos and then none of them would come out well. Now I take way less, but almost all of them come out.

Quality over quantity.

Yeah, it’s just training your eyes and knowing what you can do. You get faster, too. Do you know Samantha Fish? Have you heard of her yet? She plays blues guitar, she’s cool. I did a photo shoot with her the other day, and we finished it in like nine minutes. But I got 37 photos of her, and they had exactly what they needed. So it’s about just being confident and knowing what the result is going to be when you do a certain thing.

For sure. How do you decide what photos to include in your collections, like Instrumenthead or Instrumenthead Revealed?

I think the photos have to make you feel something. You just know. You want it to tell a story, because I think what makes a good photo is that it tells a story. So I kind of choose based on how evocative they are for me.

It’s like, you’ve got things hanging on your wall. Why are they on your wall? Because they make you feel something. Hopefully that’s not too hokey of an answer. Of course, composition, exposure, and all that stuff comes into play in the technicality of it. But ultimately, it has to make you feel.

That’s fair. Do you do anything special to capture the artists’ stories?

Definitely. Most of the time, I get them to play for me, because that’s how they really come into themselves, and I can understand who they are by listening, and then connect with that.

I think the practice from the field goes a long way, too. I’ve shot concerts for three decades, and when you shoot a live show, you’re trying to capture something. Being in the studio is different though. In the studio, you’re trying to create something. But by having that much experience with capturing photos, it gives me the skill to capture the thing that I’m trying to create when I sit down in the studio, if that makes sense. Two different skill sets, but they go hand-in-hand.

Totally. One last question for you — what do you hope for readers to get out of the book?

I want them to learn about new music and the artists who created it. A lot of these guys aren’t, you know, Bruce Springsteen or Paul Simon. It’s their trombone player, or their saxophone player. It’s in the vein of Standing in the Shadows of Motown, the Muscle Shoals documentary, or 20 Feet From Stardom. Many of these people are the sidemen; the people behind the music. You know who Joey Porter is, but how many other people know who Joey Porter is? You see what I mean? But they’re still so important and so talented, and the music is so meaningful.

There’s so much music I want to turn people on to. Because for a long time, my sister told me I used to listen to so much music because I didn’t want to hear what was going on inside my head — and I think that’s what was going on in my head through this project, making sense of it all. Music has helped me heal a lot in my life. And now I want to introduce people to great music that can help them heal too, and learn about the stories behind it.

Michael, thanks so much again for chatting today, and best of luck with the campaign and upcoming events!

Thanks for letting me tell and share my story! Good luck to you guys too.